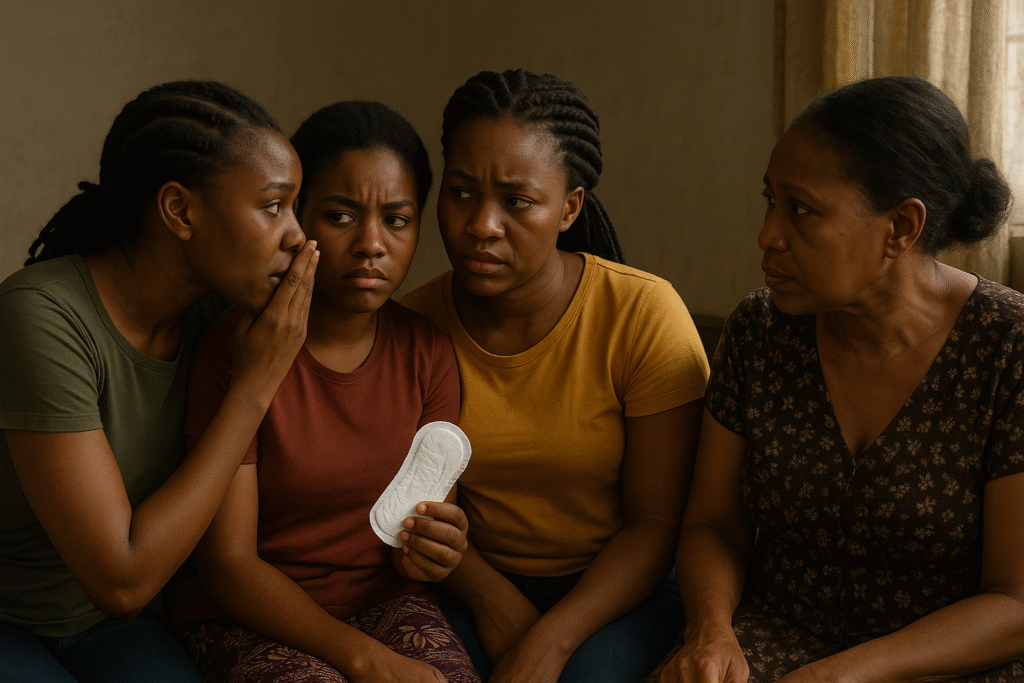

“Girl to girl… Shey na only me pad dey give wound for nyash?”, That was the single tweet that lit a match across Nigerian social media, igniting hundreds of replies from women who have endured suffering in silence.

From raw rashes to skin peeling and open wounds, Nigerian women are now openly questioning what was once considered safe: the sanitary pad.

For a product so intimate, so essential, why is this health issue only just coming to light?

THE INVISIBLE PAIN OF PERIODS

Menstruation is already emotionally and physically demanding for millions of Nigerian women. Pads, designed to bring relief and restore dignity during these challenging days, are now being blamed for doing the opposite.

“I stopped using pads. Anytime I use them, they cause itching, rashes, and discomfort. I thought maybe I was allergic to them,” said Okikiola, one of many voices in the now-viral online discussion.

Across platforms like TikTok, women are sharing disturbing experiences with comments like “It starts with itching, then becomes an open sore.” “My skin literally peels during my period.” “After five days, my inner thighs are full of wounds.”

Some women say they’ve switched to baby nappies, soft towels, or foreign products just to avoid injury. Others slather themselves in shea butter or apply anti-inflammatory creams between pad changes, hoping for relief.

“MY NYASH DEY PEEL”: VOICES FROM THE COMMENTS

A scroll through the comments section reveals a growing cry for help: “I use Ori (shea butter) to scrub and heal days after my period.” “We mummies even drag nappies with our babies.” “I thought it was just me until I saw the thread.”

Many admit they once blamed themselves, assuming it was an infection, poor hygiene, or just “sensitive skin”.

But the similarities in symptoms tell another story. And now, women who once suffered quietly are raising their voices together.

ALSO READ: Raised But Unseen: The Emotional Crisis in Nigerian Homes

REMI’S CASE OF PAINFUL PATTERNS

Remi, the lady who started the conversation on her social media platform, is 25 years of age and a corps member who lives in Abuja and never thought something as routine as a sanitary pad could become a source of pain.

“It started with itching, then it turned into a wound. I noticed it not long ago, but it happens every period. Sometimes, it even happens in public, and I’m so uncomfortable,” she told Pinnacle Daily in an exclusive interview.

She hasn’t switched products yet. “I thought it was an infection,” she admitted. “But now I know I’m not alone.”

Remi now uses Vaseline around the area before wearing a pad and applies an anti-inflammatory cream if her flow lasts longer than three days.

REGULATORY RESPONSE: NAFDAC SAYS NO COMPLAINTS YET

When asked if the Nigerian government is aware of this rising concern, the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC) says no formal complaints have been received.

Fraden Bitrus, Director of Post-Marketing Surveillance at NAFDAC, confirmed that:

- Pads are classified as medical devices and are regulated.

- Routine tests are conducted, including microbiological analysis, absorbency checks, chemical content, and physical inspection.

- Brands must list all ingredients on their labels.

- Both imported and locally made products undergo the same regulatory process.

But despite these assurances, NAFDAC admits no public petition or documented outcry has triggered any formal review or audit.

“To the best of my knowledge, we do not have safety issues with menstrual hygiene products, nor have any been reported to us,” Bitrus said.

“If we receive reports, we must evaluate the complaints and take steps to address them.”

ALSO READ: “We’re Sipping Our Way Into Catastrophe” — CAPPA Warns on Killer Drinks

THE GAP BETWEEN WOMEN AND THE SYSTEM

There lies the problem: no reports mean no action. But for many women, filing a health complaint about menstrual products is a taboo wrapped in shame. Many don’t know where or how to report. Others fear they’ll be blamed or dismissed.

And while social media is full of alarming testimonies, these digital cries haven’t yet been translated into policy or regulation.

The result? A dangerous silence.

WHEN REGULATORY STANDARDS FAIL REALITY

NAFDAC outlines a strict process for registration. Pads undergo:

- pH and absorbency tests

- Super absorbent polymer (SAP) analysis

- Microbiological tests for E. coli, S. aureus, C. albicans

- Texture, thickness, and odour evaluation

Yet some products on the market come with no ingredient list, no NAFDAC number, and no expiry date. In informal markets and roadside stores, unverified products are easily accessible and often cheaper, making them attractive to low-income women and students.

WHAT WOMEN WANT: SAFETY, NOT SILENCE

For many women, the call is simple: safer menstrual products and better oversight. They are demanding:

- A nationwide audit of menstrual hygiene products

- Public health awareness campaigns on how to report adverse reactions

- Access to safer, skin-friendly alternatives, especially for women with sensitive skin

- Affordable organic or reusable options, subsidised or included in public health programs

BLOOD, BUT NOT THIS KIND OF PAIN

Menstrual wounds – literal ones – are not supposed to be part of womanhood. Yet across Nigeria, women are nursing physical injuries and emotional frustration from something they trust every month.

The silence of regulators, the shame of speaking out and the disbelief from those in power – these are the layers of a menstrual health crisis that deserves national attention.

“Please, they should work on the pads,” Remi pleads, adding that “It’s not just my period that hurts; my skin hurts too.”

How to Report Pad Reactions to NAFDAC

Women experiencing discomfort or injury from sanitary pads can file complaints through: Email: reforms@nafdac.gov.ng

They can also submit a report online: Complaints and Enquiries – NAFDAC

Esther Ososanya is an investigative journalist with Pinnacle Daily, reporting across health, business, environment, metro, Fct and crime. Known for her bold, empathetic storytelling, she uncovers hidden truths, challenges broken systems, and gives voice to overlooked Nigerians. Her work drives national conversations and demands accountability one powerful story at a time.